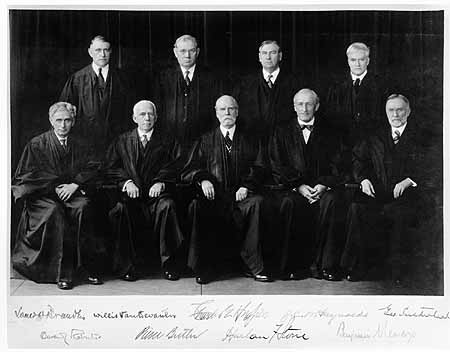

The Highest Court Hesitates

“Courts ought not to enter this political thicket.”

-- Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, declining to

intervene in a redistricting case (Colegrove v. Green, 1946).

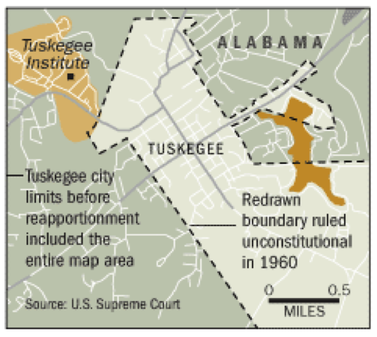

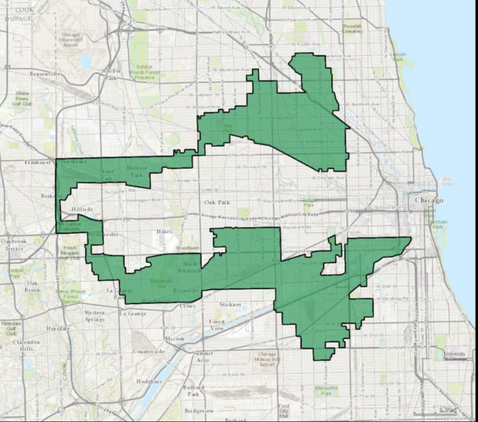

The judicial branch was called upon to review legislative curbs

on redistricting abuses. The Court’s engagement, however,

created more confusion than clarity.

on redistricting abuses. The Court’s engagement, however,

created more confusion than clarity.