Cracks Turn Into Chasms,

A Nation Struggles to Respond

“It was impossible to foresee all the abuses that might

be made of the [States’] discretionary power.”

be made of the [States’] discretionary power.”

-- James Madison, in his “Notes of Debates of the Federal Convention of 1787,”

referring to the risks of allowing States to govern their own congressional elections.

referring to the risks of allowing States to govern their own congressional elections.

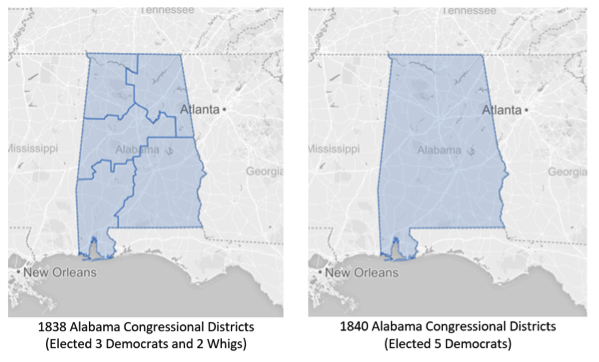

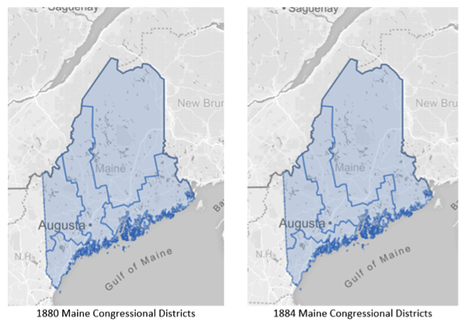

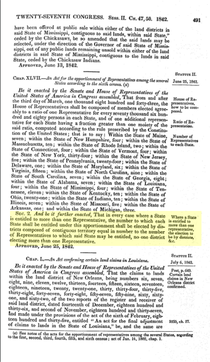

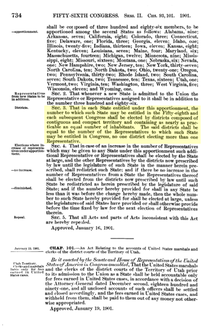

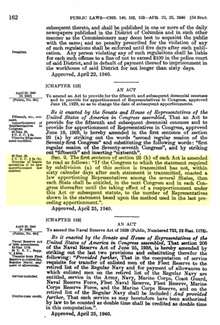

As manipulation of district lines becomes more pervasive, Congress

tries to take action, but struggles with bickering politicians and

assertive States. The bipartisan, democratic ideals outlined at the Constitutional Convention start tragically slipping away.

tries to take action, but struggles with bickering politicians and

assertive States. The bipartisan, democratic ideals outlined at the Constitutional Convention start tragically slipping away.

Student interview with George Mason University professor Rosemarie Zagarri, an expert in early

American representative government, conducted on April 1, 2019 via a Skype videoconference.

American representative government, conducted on April 1, 2019 via a Skype videoconference.